Scottish Defence Policy I: The Utility of Military Force

Considering the defence policy of an independent Scotland

This is the first post in a series looking at the defence policy of a future independent Scotland. In this series I'll be looking at United Kingdom defence policy, its strengths and weaknesses, comparing it to some other countries, and making some suggestions regarding the defence policy of an independent Scotland.

Articles for Scottish Defence Policy

Scottish Defence Policy 1: The Utility of Military Force — this post

Scottish Defence Policy 2: nation and army comparisons compares the British army with some others and asks why they are different

Scottish Defence Policy 3: Scotland's Army notes that independent Scotland could easily have a bigger army than the UK

Scottish Defence Policy 4: Drones including lessons learned from Russian use of the Iranian Shahed-136 drone in Ukraine

An alternate history scenario, imagining if Scotland had voted for independence in 2014:

Scottish defence policy 6.1: If we'd voted for indy in 2014, what might the Scottish armed forces look like today?

Scottish defence policy 6.2: The Scottish army in 2024, 10 years after we voted to leave the UK

In this first post, I'll be asking "What's the point of military force anyway?"

The origin of states

Sociologist Max Weber defined a state as any organisation with a monopoly of legitimate force over a geographical area. And science fiction writer Ken MacLeod noted that war is the state's killer app.

Weber mostly had in mind the state's apparatus for internal violence -- police, courts, prisons, etc -- but without an apparatus for external violence -- an army -- a state could easily be gobbled up by a rival. As Dr. Bret Devereaux put it:

The goal of survival in a dangerous world in turn suggests that maximizing security is the highest external priority of the state. Since historically, the greatest threat to state survival was foreign military action (read: being conquered) is makes sense that the kind of security being maximized is military security. In turn, maximizing military security generally means maximizing revenue and manpower. So a state whose goal is to survive is likely to seek to maximize state power, to draw in as much manpower and revenue as possible.

States are one of the most effective methods humans have created for solving co-ordination problems (i.e. getting lots of people to act together towards a common endeavour) and they've been so successful that while 5000 years ago only a small part of the inhabited earth was controlled by states, today all of it is.

A big part of the reason for the success of states is that states with armies will almost always beat non-state societies.

Armies

So what is the use for armed forces? As I've suggested above, one big use is to conquer a rival country. And that leads naturally to the converse: to prevent being conquered by a rival state.

Before the industrial revolution countries often conquered rivals to acquire their territory and make it part of the conquering state. This was because wealth came from controlling land and appropriating the surplus wealth of farmers, and it was a lot easier to conquer more land that to increase the productivity of one's citizens.

(One of the most recent attempts to gain land by conquest was the German invasion of Russia in 1941. Germany intended to exterminate the native Russians and repopulate the land by German farmers, and they also wanted to gain access to Russia's rich mineral resources, which Germany was relatively lacking in, and which Hitler thought it was necessary for Germany to control in order to be rich and powerful.)

Conversely in the present day, it's relatively easy for a state to increase the productivity of its citizens (indeed states today generally grow their economies by 2-3% or more year on year) but difficult to make conquered territories productive.

So, in the modern world, when one country defeats another, they don't usually absorb the new territory into their own state, They keep it as a separate state and install a new government in it, one that will do their bidding: a client state. Examples include the Soviet rule in Eastern Europe from 1945-1990, or the US-backed government of Afghanistan from 2001-2021. (The USA conquered Afghanistan because the previous Afghan government, the Taliban, was harbouring al-Qa'ida, who had committed terrorist acts against the USA, and the USA wished to replace it with a more friendly government. The USA also wished to transmit liberal democratic values to the Afghans, in the hope this would make Afghanistan a country which over the long term is aligned with the USA politically. I will just note here that changing a country's values is not an easy undertaking.)

As well as conquering all of another country, a country might just conquer part of it. A current example is Ukraine, parts of which are currently occupied by Russia. (The motivation of the Russians is to prevent Ukraine becoming aligned to the West by joining the EU and NATO -- Russia hopes that having a frozen conflict will hinder Ukraine's ability to become part of the West, which Russia sees as an adversary.)

Armed force can also be used to destroy targets in an enemy country, such as military bases, or infrastructure.

Or at sea, a country can blockade another country's ports and prevent it from conducting trade. A lot of the world's trade is carried by sea, and island nations such as the UK, Japan, Indonesia, or Australia are obviously dependent on the sea for imports, since bulk goods cannot be economically delivered by air.

And most of all military force can be used to threaten some or all these things unless the threatening power gets its way on some issue. The threat of force is a good deal more common than the actual use of force. Indeed, the very existence of armed forces is itself an implied threat: it is saying "Don't do things we don't like, because if you do, we can make things difficult for you".

Finland: a case study in deterrence

In 1944, Russia was fighting Germany as well as Germany's allies: Finland, Hungary and Romania.

Russia would have been able to conquer Finland, but because Finland had put up a very good fighting the Winter War and Continuation war, decided it would suffer heavy casualties in doing so. Furthermore, Germany was not yet beaten, and Russia would need lots of men to beat Germany. So the Russians allowed Finland to conclude a separate peace and stay unconquered.

Finland did lose some territory, notably Karelia, Salla and Petsamo (see map below). Finland also had to give up the region of Porkkala to the USSR between 1944 and 1956.

A small country thus often doesn't need to be able to win a war against a larger one; it merely needs to make the adversary believe that the costs of aggression will not be worth the benefits. Thus Finland was able to deter even Stalin, who was not someone who showed any concern for the lives of his countrymen and thus was quite prepared to throw away lives.

Trade sanctions

In the modern world when countries want to threaten other countries, they often don't use violence, instead they threaten to not buy the other party's goods, or to not sell some strategic good. Strategic goods might be raw materials that're necessary for lots of technologies but which only a few countries have (for example oil, or tungsten or rare earths), or they might be military technologies and weapon systems.

Trade sanctions case study #1: Trade sanctions and Northern Ireland

A good example of the threat of trade sanctions was over Brexit. The Irish government's interpretation of the Good Friday Agreement is that there should not be tariff or non-tariff barriers across the border between Northern Ireland or the republic of Ireland, making it necessary to have custom controls between Great Britain (GB) and Northern Ireland (NI), even though GB and NI are parts of the same country. Britain, on the other hand, wanted Northern Ireland to be part of the UK's trading area and didn't want trade barriers between GB and NI.

But Ireland was in the EU, and the EU was able to make the implied threat: do what we want or we won't buy your goods. So the UK had to reluctantly acceed to Ireland's position on the inter-Ireland border.

Trade sanctions case study #2: Actual war trumps trade war

While trade sanctions often have bite, it must be remembered that actual war trumps them.

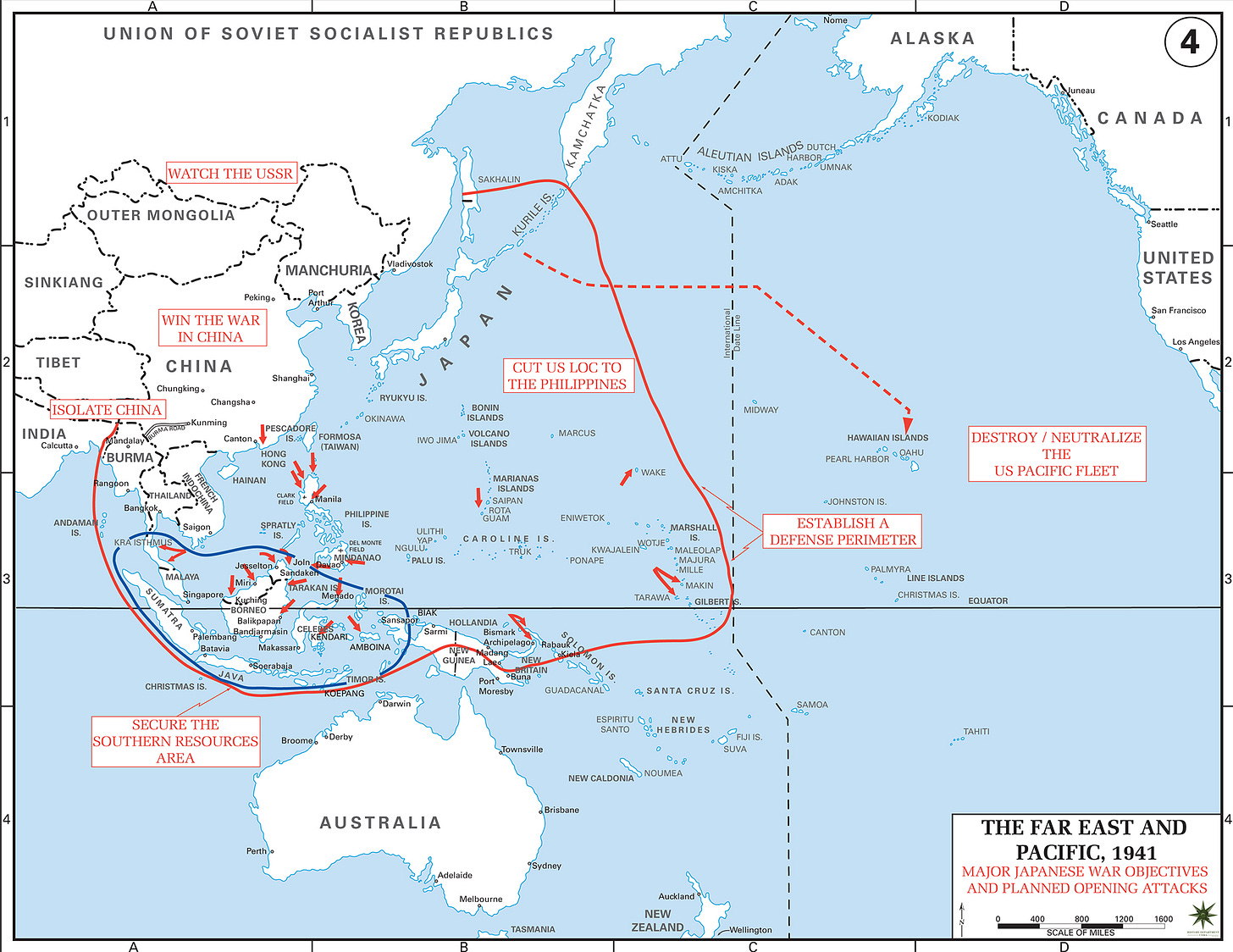

Consider that in the summer of 1941, the USA refused to sell oil to Japan, and persuaded other countries to not sell oil to Japan either. They did this in order to put pressure on Japan to withdraw from China and French Indochina (modern Vietnam). Japan, instead of withdrawing, started a war against the USA, the Netherlands and Britain, and seized the oilfields of the Dutch East indies (modern Indonesia, the oilfields are on the islands of Sumatra and Borneo on the map below).

The USA eventually won that war, but the whole incident demonstrated that trade sanctions can be nullified by brute military force, and that therefore if a country is thinking about hurting a rival with trade sanctions, it needs to bear in mind that its rival might respond militarily.

How does this relate to an independent Scotland?

We've seen how military force can be used to invade and occupy other countries, to coerce them into doing what one wants, and importantly to deter others from doing these things to oneself.

Considering a future independent Scotland, it's clear that Scotland as a small country is unlikely to threaten others. Its people don't want to nor is it big enough to be able to.

But Scotland does have a very big interest in avoiding being coerced by others. Having capable armed forces helps achieve that, as does joining a defensive military alliance such as NATO.

As we've seen, military threats are not the only type of threat. Scotland also needs to be secure against threats of trade sanctions, and joining the EU would be very helpful there.

It's a potentially scary world out there, but with its own strength and with a network of alliances with other rich democratic countries, Scotland can weather any storms.

(When we talk of Scotland having a "network of alliances" some might level the accusation that Scotland will be merely exchanging one master (the UK) for another (the EU and NATO). I disagree with this accusation, as Scotland would have more autonomy in the EU than the UK.)